BY FORTUNE MOYO

While waiting for customers, Sikhulile Ngwenya, a local vendor at the Mkhosana market, carefully loads her stall with cabbages, carrots, avocados, tomatoes and choumolier, a dark green, spinach-like vegetable with slightly crumpled leaves.

A faint sound of local music playing on the radio at a shop not too far away reverberates through the market.

Housed in a red-brick structure, the market — one of two in Zimbabwe’s Victoria Falls city — is divided into 20 stalls, including Ngwenya’s, all displaying a variety of vegetables and fruit, neatly and attractively packed.

It is a busy area just behind a small shopping center where taxis drop off and pick up Mkhosana residents.

This has been Ngwenya’s source of livelihood for more than 10 years.

“I have raised my four children from this vegetable stall,” she says. But today she feels a constant threat and uncertainty looming over her livelihood.

The reopening of the Zimbabwe-Zambia border, more than two years after it was closed in 2020 as a precautionary measure to combat the coronavirus pandemic, paved the way for the return of vegetable vendors from neighboring Zambia.

And even though the informal cross-trading relationship between Zambia and Zimbabwe has long been mutually beneficial, the return of Zambians has rattled vendors like Ngwenya, who say that their profits plummeted since the opening and that the competition is no longer fair.

The “good business” during the pandemic has made Zimbabwean vendors realize, Ngwenya says, that Zambians are making money illegally “in our territory at no cost” and demand they be brought under the purview of law.

Zambia and Zimbabwe share similar social and cultural practices, making the movement of people between the countries easy.

Zambian vendors cross over from the nearby city of Livingstone in their country to sell vegetables to residents of Victoria Falls, a tourism city on the Zimbabwean side.

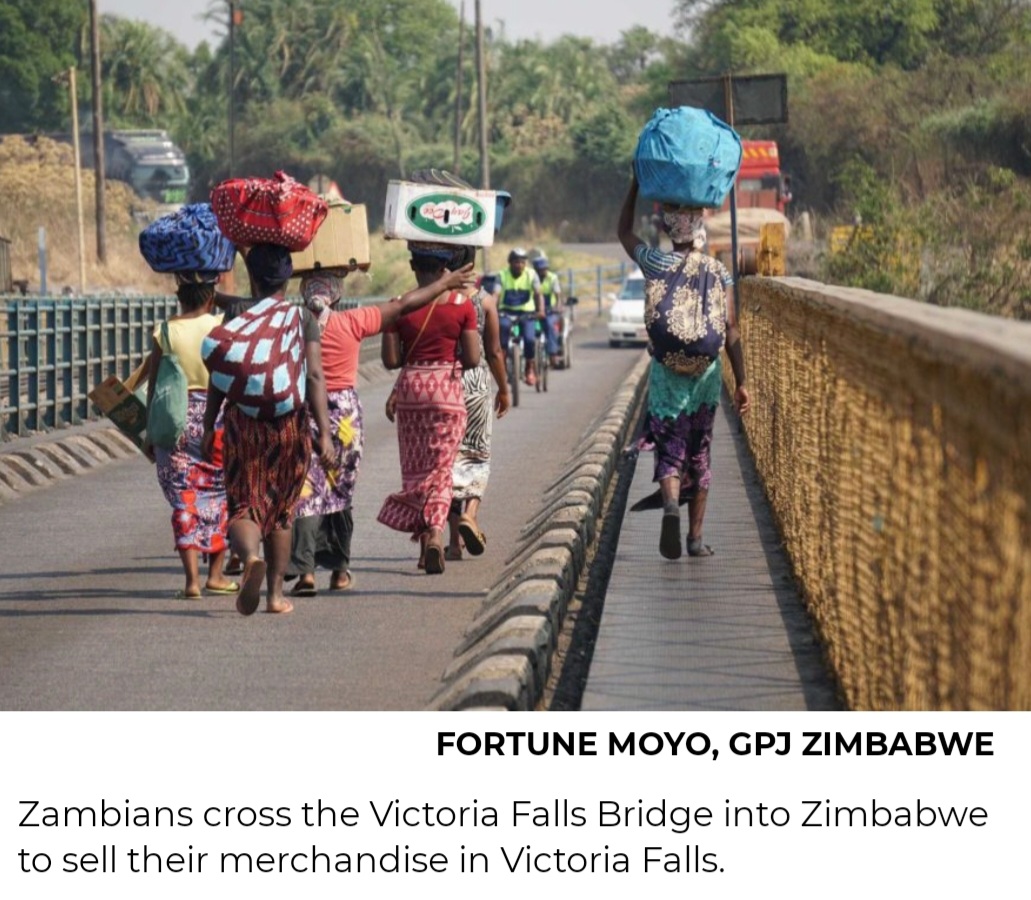

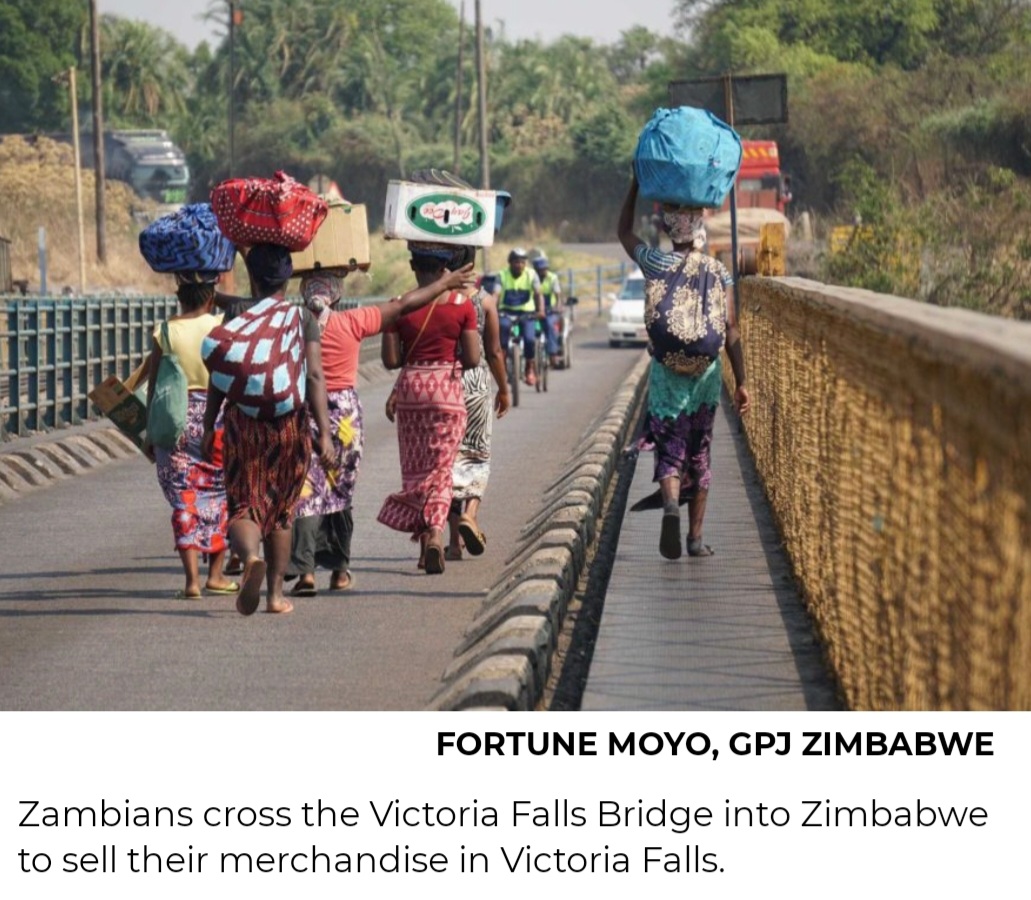

In the early mornings, the Zambian vendors, popularly known as omzanga, a Nyanja term meaning “friend,” cross the Victoria Falls Bridge — the only route from Zambia to Zimbabwe.

The omzangas can easily be identified by the effortless way in which they balance the containers loaded with vegetables on their heads, or the carefully tied merchandise on their backs, wrapped with bright, colorful fabric in bold designs, popularly known as zambias.

When borders were closed here like elsewhere globally, cross-border trade was allowed only for the movement of large commercial goods, not for people.

As a result, local vendors enjoyed a monopoly over the market because customers had no option but to buy vegetables from them, even if their prices were higher than those of their Zambian competitors.

But local vendors say locals know and understand the reasons for the higher prices.

The farms in Zambia are close by. As a result, the Zambian vendors always have easy access to fresh fruit and vegetables.

Local vendors, on the other hand, have to get their vegetables from places like Lupane, 264 kilometres (away; Bulawayo, 435 kilometres away; and sometimes as far as Harare, 874 kilometres away, because those are the closest farms to Victoria Falls.

This forces them to sell at higher prices because it costs more to acquire the produce.

It doesn’t help that local vendors must operate from their designated spots in the markets, for which they pay rent to the municipality, while the Zambian vendors can move door to door.

Ngwenya, who pays the Victoria Falls municipality $16 a month for her stall, says during the first government-mandated coronavirus lockdown, she made US$15 to US$25 a day, but now she makes US$10 to US$15 a day.

“Because vendors sell door to door, our customers no longer visit the market,” says Ngwenya.

“This is now a threat to our livelihoods as we no longer sell much, because residents would rather wait for the Zambian vendors sitting in their homes.”

The pandemic gravely affected tourism here, and many people were laid off.

With no Zambian vendors in the picture then, many Zimbabweans took up selling vegetables as a means of livelihood.

But after the border opened, and months later when restrictions were lifted completely, they realized that Zambians were “stealing” the local clientele and they needed to address the issue, says Grace Shoko, vice chairperson of the Zambezi Informal Cross Border Traders Association.

Shoko, whose organiSation was founded in late 2021 in Victoria Falls to resolve issues between local and Zambian traders, says representatives of the association have spoken with authorities and vendors from both sides of the border, to try to find a workable solution.

Naomi, a Zambian vendor who prefers that only her first name be used for fear of being targeted, says when she sells in Zimbabwe, she makes more money than when selling in Zambia because in Zimbabwe she sells in United States dollars, which she converts to Zambian kwacha back in her country, giving her a substantial amount.

“I understand that it is unfair that locals are not allowed to sell door to door, and we can,” she said.

“However … I am also doing what I can to support my family in Zambia.”

Exact figures for informal cross-border trade are hard to come by because of its unrecorded nature, but such trade constitutes a major form of informal activity in most African countries.

In fact, in the Southern African Development Community (Sadc), which includes Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia and Zimbabwe, cross-border trading has an estimated value of about US$17.6 billion, which accounts for 30% to 40% of intra-Sadc trade.

Even though informal cross-border traders carry different types of goods, trade in sub-Saharan Africa is dominated by food, particularly groceries and fresh produce.

Until recently, Zambian vendors coexisted with local vendors, without any large-scale resentment or demands.

But now, as most coronavirus restrictions have been lifted, easing the movement of people, some vendors have come together to express this displeasure collectively, with the help of organisations like the Mkhosana vendors association, lobbying for a level playing field and an end to what they say is an undue advantage for Zambians.

Mercy Mushare, a member of the Mkhosana vendors association, says the group is in talks with the municipality to put in place bylaws that protect local vendors or build stalls for Zambian vendors.

“We are not saying Zambians should not come and sell, but they should abide by the same bylaws which we abide by.

They should not be at an advantage over locals,” says Mushare. (The association has a membership of about 300 vendors.)

The city’s bylaws stipulate that vendors should sell from designated places and not move around the city.

But the laws apply only to local vendors.

Mandla Dingani, spokesperson for the Victoria Falls municipality, says the municipality is well aware of the tension between omzangas and local vendors.

“We are in the process of coming up with a way of ensuring that even Zambian vendors sell from designated stalls and also pay a monthly fee for selling in Victoria Falls,” Dingani says.

Sibusiso Dube, a resident of Chinotimba, worries that strict action against Zambian vendors might eventually hurt the common Zimbabwean.

“It is unfair for Zambian traders to have more freedom … but if Zambian traders are barred totally, we will suffer because local vendors will increase their prices of vegetables beyond the reach of many, as we experienced when borders were closed during Covid-19,” he says.

Standing in front of her stall, Ngwenya says what she knows is that she is suffering losses. Despite that, this is the only work she has known over the years, and switching to anything else now is out of the question for her. – Global Press Journal

Slider3 years ago

Slider3 years ago

National4 years ago

National4 years ago

Opinion3 years ago

Opinion3 years ago

Tourism and Environment4 years ago

Tourism and Environment4 years ago

National2 years ago

National2 years ago

National3 years ago

National3 years ago

National2 years ago

National2 years ago

National4 years ago

National4 years ago