BY MICHEAEL DAVIE AND MATT HENRY WITH PICTURES FROM KYLE JIRA

There’s no delicate way to bore a hole in the horn of a two-tonne white rhino still twitching under the effects of an immobilisation dart to the rump.

So Colin Wenham goes at it with a yellow battery-powered drill, each plunge of the whirring drill bit sending shavings of white keratin – the stuff fingernails are made of – curling through the air.

They pile up at our feet, like snow in the red African dirt.

On the black market, rhino horn can sell for more than its weight in gold.

While it has no proven medical benefits, some believe its powdered form has near mythical powers of healing, curing ailments from hangovers to cancer.

Soaring demand in China and Vietnam has fuelled a thriving business for ruthless poaching syndicates across southern Africa.

After trophy hunting in the 19th century and rampant poaching in recent decades, one of Africa’s most iconic animals – the black rhino – has been driven to near extinction.

Cruel economics make them more valuable dead and dehorned than alive.

But this rhino will keep its horn. Colin, Malilangwe’s deft and experienced wildlife manager, is carefully fashioning a neat cavity to insert a GPS tracker, roughly the size of a box of matches, at the horn’s base.

The process looks brutal but if done above the growth plate is as painless for the rhino as clipping your fingernails.

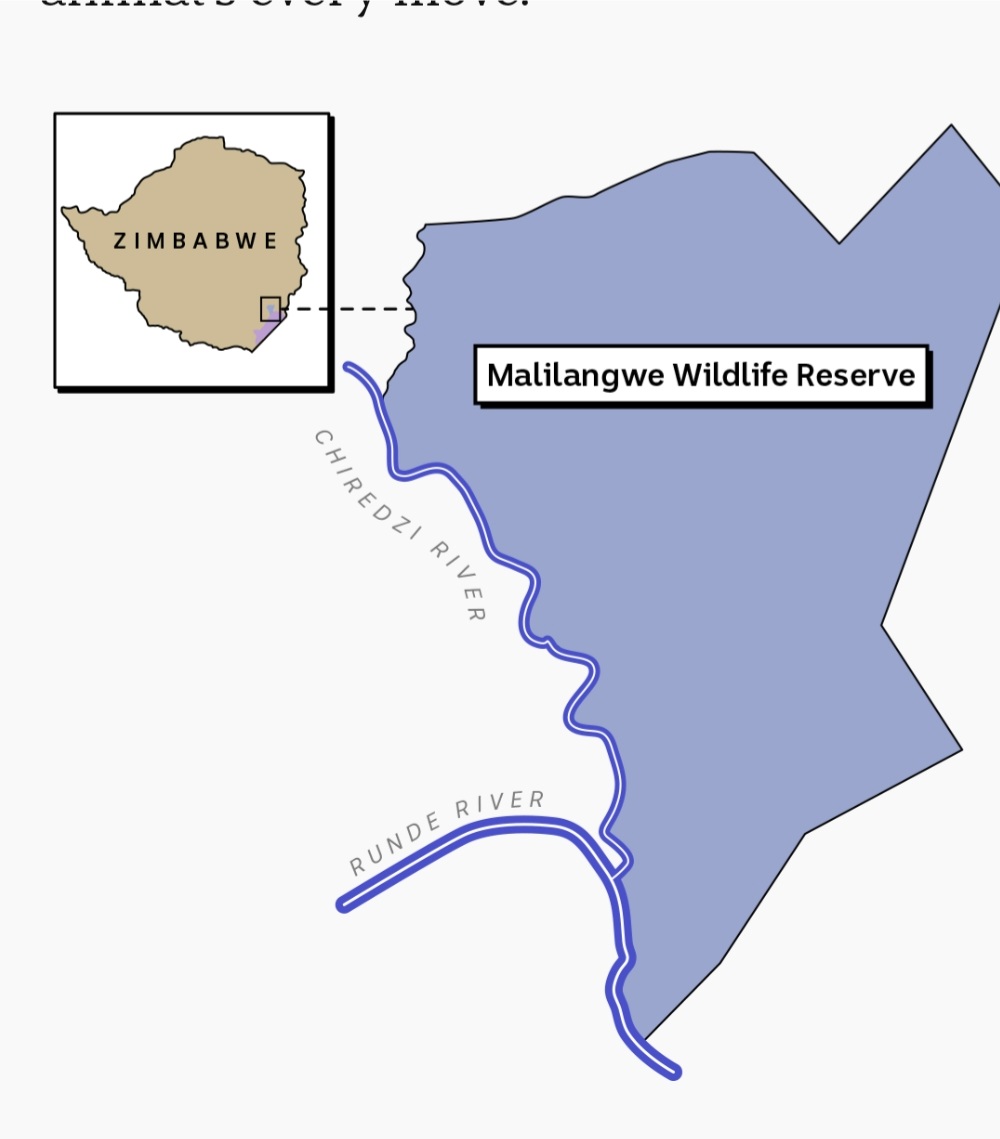

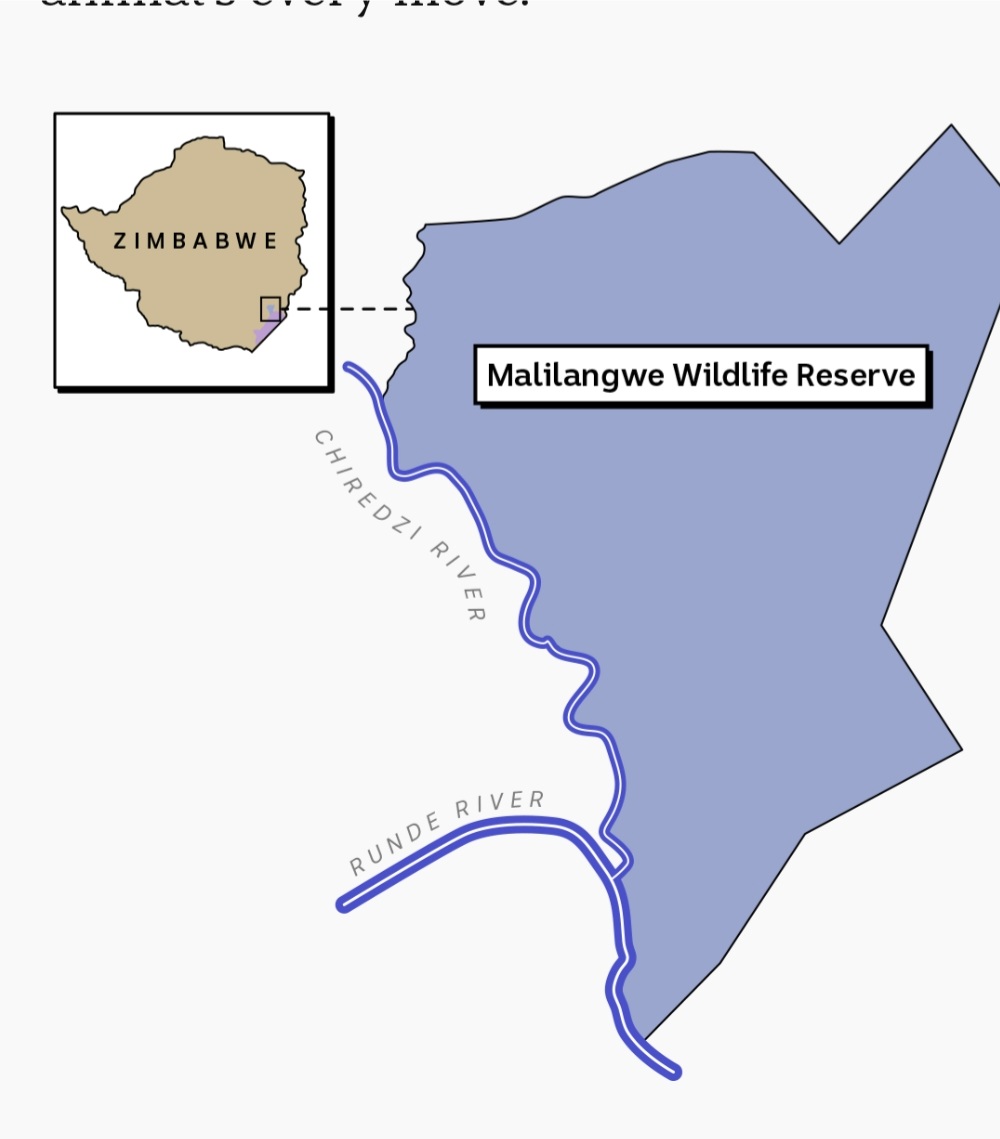

When the job is complete it will better enable the scientists here at the Malilangwe Trust, a 50,000-hectare private nature sanctuary in south-eastern Zimbabwe, to track this animal’s every move.

It’s conservation techniques like this that have helped Malilangwe become one of Africa’s most successful rhino sanctuaries.

Over the past two-and-a-half decades, it’s played an outsized role in bringing the black rhino, one of the world’s most endangered animals, back from the brink.

It’s also had remarkable success boosting white rhino numbers.

Starting with a few dozen rhinos in 1998, the park’s black rhino herd has increased by more than 600 per cent and its white rhinos by 900 per cent, even as waves of poaching across Africa decimated rhino populations elsewhere.

Over 400 rhinos now roam the park.

In fact, Malilangwe has a startling new problem – it could soon have too many rhinos.

Like a modern-day Noah’s Ark, it is now repopulating other corners of Zimbabwe, returning rhinos to natural habitat where they haven’t set foot for decades

olin screws the tracking device into the rhino’s horn and seals up the gash with a wodge of epoxy.

The immense 17-year-old bull is lying awkwardly on his side, legs protruding outward.

Each snort of breath kicks up plumes of dust. It took a team of handlers to roll him into this position so he can breathe more easily.

The pulsing blip of an oxygen monitor fades in and out as a helicopter thunders in circles overhead.

A dozen people crowd around, vets, scientists, everyone moving quickly.

They’re trying to keep the rhino comfortable in the baking afternoon sun as they work.

The drug used to immobilise the animal – delivered via dart from a helicopter-mounted veterinarian – can interfere with its heat regulation, so a handler mists the rhino’s leathery skin with water to keep it cool.

The rhino has been sedated with a drug so powerful it can be fatal to humans.

His tech upgrade complete, he’s injected with another drug to reverse the sedation.

From a safe distance, we wait for him to stir back to life.

Within minutes he lumbers to his feet, casting a baleful glance in our direction before turning and disappearing into the bush.

It’s day three of what they call “rhino ops” at Malilangwe, a frenetic week-long mission to check on the health of the park’s rhinos and gather vital data about the state of the herd.

Over the next four days they’ll take blood and DNA samples from a dozen more rhinos and notch calves’ ears with a unique ID pattern.

Sarah Clegg, an ecologist with an encyclopedic knowledge of rhinos, is overseeing the operation, scribbling notes on her clipboard.

“In an ideal world, we wouldn’t touch these animals,” she says.

“But because of the challenges we have with poaching and the reduction of habitat, we do need to know what’s going on so we can manage them in the best way possible.”

The more the park knows about its rhinos, the better its can protect them, she says.

Sarah, who has been studying black rhinos for 25 years, says the data these GPS units beam back will have “huge implications for helping us understand how rhino use the landscape throughout the day.”

It will show how far they roam and where they cluster in the park.

It’s invaluable information as Malilangwe now looks to find suitable homes for its rhinos in other parts of Zimbabwe where they have been virtually wiped out.

“That helps us to choose areas that are going to meet their needs,” she says.

Across Africa, there’s a dire need to rebuild rhino populations after decades of habitat loss and poaching.

At the turn of the 20th century, it’s estimated half-a-million rhinos roamed Africa and Asia.

Today that number stands at just 27,000, with most behind protective fences in private reserves, or in a select number of national parks with the resources to resist poachers.

Few now can survive in the wild, where they are easy prey.

Africa’s poaching problem has come in a series of waves over the past four decades, with the most recent crisis kicking off in 2008.

In South Africa, home to the world’s largest rhino population, just 13 rhinos were killed by poachers in 2007.

In the seven years that followed, the annual toll rose a staggering 9,246 per cent, peaking in 2014 when 1,215 rhinos were killed.

Conservationists’ hopes that the poaching problem had been brought under control were shattered.

Across the African continent, 11,000 rhinos have been killed by poachers since 2008.

While poaching has gradually declined in more recent years, it’s never returned to the low levels seen in the early 2000s.

Last year, poachers killed more than a rhino a day.

“The demand for rhino horn is so high there’s no shortage of people who are prepared to poach,” says Sarah.

“The need in Africa is so great there are people willing to take those risks.”

When the not-for-profit Malilangwe conservancy was founded in 1994, Zimbabwe’s white and black rhinos had already been decimated. Black rhinos in particular had been hard hit by poachers.

By 1998, the conservancy had imported 28 black and 28 white rhinos from South Africa and set out on what might have seemed a quixotic bid to turn a vast tract of land degraded by cattle ranching into a sanctuary where native wildlife could flourish.

The conservancy began an intensive monitoring and protection program, mostly funded by private donors as well as tourism ventures in the reserve.

“Protecting rhinos is difficult, it costs a lot of money,” says Malilangwe’s executive director Mark Saunders.

“It takes experience. It takes a lot of time, it takes a lot of patience and energy.”

Back out in the field, the scale of a modern-day rhino conservation operation is on full display.

The helicopter lurches back into the sky.

The ground team piles into four-wheel drives.

The rhino ops caravan moves to the next location. There are three more rhinos to check today.

Family ties

Under the shade of a frayed green tarpaulin, her moistened skin has the dark sheen of new bitumen.

She’s just a calf, a 17-month-old black rhino, powerful and yet delicate too.

A vet is feeding her oxygen through a clear plastic tube, conscious that the immobilising drug could suppress her respiratory system.

The calf’s mother is likely lurking somewhere close by, says Sarah.

They flee the clamour of the helicopter but the maternal bond is strong with a calf this young.

The vets clamp her ears with two pairs of forceps in the figure of a V, then uses surgical scissors to remove a triangular slice of the ear.

A hairy wedge tumbles onto the rippled fold of skin above her shoulder blades.

These “notchings” are a kind of code used to identify the rhinos at Malilangwe.

Each notch corresponds to a number, depending on where it’s positioned on the ear. Add them up and you get that rhino’s unique ID.

Conducting this procedure while rhinos are so young is a necessary evil, Sarah explains, because mothers cast their calves away when they are around two years old, when cows typically give birth again.

“So we need to notch this calf while it’s with its mother,” she says, “so we can record which calf belongs to which mother.”

Sarah is actively mapping the maternal lineage of all the rhinos in the park.

Tracking them so closely has already revealed some surprises, like the fact black rhinos – often thought of as solitary and ill-tempered creatures – maintain close family bonds with their mothers into later life.

Some bulls as old as eight have been observed visiting their mothers from time to time, she says.

“They’ve got this reputation of being bad tempered and dangerous, and they are.

“ But I think it’s mostly that they’re just such emotional creatures.

“They’re just insecure, you know?”

It’s more than mere scientific curiosity driving Sarah’s focus on the rhinos’ emotional lives.

Understanding their social bonds will be the key to successfully moving rhinos to another park in the future, she says, a process known as “translocation”.

These big beasts are sensitive souls.

Ignoring it can end in catastrophe if they’re moved to an unfamiliar location without their close companions.

“In the past we’ve made it convenient for ourselves not to consider the emotional attachments that animals have and their feelings,” she says.

“But it’s a truth we need to face.”

Last year, Sarah’s theories were put to the test when 10 of Malilangwe’s black rhinos were translocated to neighbouring Gonarezhou National Park.

In the early 1980s, Gonarezhou was ground zero for poachers.

The jewel in Zimbabwe’s wildlife crown had its rhinos completely wiped out.

It took Sarah years to carefully select the best possible group of rhinos to be translocated together.

Their social bonds were one of the key considerations to help ease the transition into their new home.

“Happy animals can produce more babies,” she says.

“That can grow more populations. And that’s what we need with rhinos.”

In May 2021, the big move began.

Malilangwe was one of three private parks who together translocated 29 rhinos to Gonarezhou.

At 5,000 square kilometres, Gonarezhou is 10 times as big as Malilangwe and has the infrastructure and resources to handle an influx of rhinos.

After a few weeks in fenced “bomas” to monitor their condition, the rhinos were released – the first to set foot in Gonarezhou National Park in nearly 30 years.

Reintroducing rhinos to the park was an historic moment for Zimbabwe.

“It’s extremely rewarding,” says Sarah, thinking back to that day.

“Being able to put a rhino back into that park is like waking it up again.”

You can’t help but feel Patrick Mangondo is being modest when he says he was “a little bit tiny” at school.

The shortest in his class, he says.

These days the burly 42-year-old cuts an imposing figure as he emerges from the African scrub at the head of a small column of black booted, khaki-clad men, each with an automatic rifle slung over his strapping frame.

Patrick is a sergeant in the Malilangwe Scouts, an elite anti-poaching unit and private security force tasked with protecting all the animals – and people – within the Malilangwe conservancy.

“Most people see rhinos as money left on the ground,” Patrick says. But rhinos have the right to live, “the right to be protected,” he says.

Malilangwe hasn’t been immune from the scourge of poaching over the years.

It’s “always a threat,” says Sarah Clegg.

“We still do have incursions. It’s something you have to stay on your toes with.”

Poachers have breached the park’s boundary 10 times since 1998, killing and dehorning three adult rhinos during three of those incursions.

A fourth rhino – a calf – died after its mother was killed in one of those attacks.

On seven other occasions, Scouts foiled the attack before any rhinos could be killed.

Each day the Scouts break into groups to patrol the park’s 120km fence-line on foot, monitoring for rhinos and searching for signs of poachers.

Extreme dedication to fitness and physical strength is one of the demands of the job.

Confronting poachers is a dangerous business. Patrick speaks of it as a war.

“If they come, they’ll bring war to us,” he says.

It’s a war that’s playing out in private wildlife sanctuaries and national parks across Africa.

A record 92 rangers died in 2021, half of them in homicides.

In July, the lead ranger at South Africa’s Timbavati reserve, Anton Mzimba, was fatally shot outside his home in circumstances akin to a hit job.

His brazen killing has stoked fears organised poaching syndicates are actively targeting wildlife protectors.

Patrick’s wife Tari worries for her husband. She prays daily for his safety.

But “it’s very important to have a job, and they’re not easy to find,” she says. “So once you have a job, thank you Jesus.”

Many of the Scouts were once small-game poachers themselves.

A young man named Exodus tells how he started poaching after his brother taught him how to hunt.

“Most traditional people, they like to hunt,” he says.

“Like, culturally,” he clarifies. Many turn to poaching simply to put food on the table, targeting small wildlife species like Impala.

But their tracking and bushcraft skills can be turned into assets for conservation.

Providing well-paid jobs in the surrounding villages is itself an anti-poaching strategy, says Mark Saunders.

“It’s one of the most often discussed phenomena in conservation circles, how to integrate communities, how to mitigate against human-wildlife conflict,” he says.

“We feel that education is very important and we have a bespoke conservation education camp here.

As human populations encroach further on protected areas, the potential for conflict with wild animals is only increasing.

“If [local people] see an elephant in the fields, this means their crops are going to be devastated,” says Sarah Clegg.

“If there’s a lion, there’s a chance their livestock is going to be taken.”

She says teaching the inherent value of preserving Zimbabwe’s wildlife heritage is essential for safeguarding conservation efforts.

“I would say maybe 90 per cent of Zimbabweans haven’t seen a rhino,” says Patrick.

“Only on television. We want them to help us and preach that word —

These animals are not for being poached for money, everyone needs to know the rhino is special.”

To that end, Patrick helps lead the Junior Rangers program, a community outreach initiative that brings underprivileged teens to Malilangwe to study physical fitness, bushcraft and ecology.

He’s also taken an active role in training the rangers at Gonarezhou National Park in how to track, monitor and care for its new rhino population.

“Individually you can’t win against poaching,” he says.

“We need to be like brothers. You have to be a team, a strong one, to win this fight.”

Return of the rhinos

It’s been a year and a half since the black rhinos were translocated to Gonarezhou National Park and Patrick has come back to meet Richard, one of the rangers he trained to care for Gonarezhou’s new residents.

“They taught me everything, including how to tell the difference between a black and white rhino spoor,” Richard says. “I’m grateful for the knowledge they gave me.

Together they head into the park’s 700 square kilometre “intensive protection zone”, or IPZ, a fenced area within Gonarezhou where the rhinos are being kept.

After a few hours spent tracking, we catch a glimpse of a rhino calf born inside the park, one of five new births since the rhinos were moved here.

It’s an encouraging sign the rhinos are comfortable in their new home.

“It makes me feel good and happy because I now know that these guys are taking care of the rhinos,” Patrick says.

“They’re not abandoning them, they’re doing a great job.”

It’s wondrous, but fragile.

Everyone involved in getting rhinos back into Gonarezhou knows the years, indeed decades, of work could be swiftly wiped out by poachers. “So far it’s been a success,” says Sarah.

“It’s a sign we’re winning the war on poaching. It’s scary though, you can say that today and tomorrow it’s something else.”

Sarah knows it’s only through continued vigilance and hard conservation work that rhinos will still be here for her grandkids to enjoy.

“It would be a great tragedy that something like this was lost over time,” she says.

“I’m certainly going to make every effort we can to make sure that it’s not lost – ABC

Slider3 years ago

Slider3 years ago

National4 years ago

National4 years ago

Tourism and Environment4 years ago

Tourism and Environment4 years ago

Opinion4 years ago

Opinion4 years ago

Special reports4 years ago

Special reports4 years ago

National4 years ago

National4 years ago

National3 years ago

National3 years ago

National3 years ago

National3 years ago