BY OWN CORRESPONDENT

In the decade following possibly one of the worst poaching incidents in southern Africa, which left at least 300 elephants dead after poachers laced watering holes and salt licks with cyanide, crimes against wildlife have drastically declined in Zimbabwe’s largest national park.

Yet the sad memories remain vivid for the frontline rangers who experienced it firs thand.

In 2013, on a typical Saturday morning in the middle of a rainy season, an anti-poaching unit that patrols Hwange National Park was on a routine patrol of the southern part of the massive reserve, known as the Makona area.

A seasoned ranger with impeccable bush experience, 42-year-old Katenda Tshuma, suddenly signalled the driver to stop after he caught an overpowering rotten stench.

The sight of vulture feathers and droppings on the ground indicated that a carcass was nearby.

At this park, just like any other wildlife reserve, death is announced by scavenging and carrion-eating birds of prey.

Ten minutes into the search, Tshuma set his eyes on a horrifying sight—a decomposing male elephant.

The following morning, extensive ground and air surveillance around some of the less accessible areas of the park revealed grimmer news.

“We discovered more than 20 carcasses around the extensive search area.

“It remains one of the most devastating experiences of my career,” he says.

Investigations conducted by the Zimbabwe National Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZimParks) revealed that the deaths were due to cyanide poisoning.

“The horrendous crime, which made international headlines in 2013, led to the deaths of an estimated 300 elephants and is believed to have been carried out by well-organized poaching syndicates.

For Tshuma and the other brave individuals tasked with protecting Hwange National Park, the catastrophe was a wake-up call: The mission to safeguard elephants was more critical than they had ever imagined.

“The terrible event didn’t kill our passion and desire to protect the gentle giants in the wild,” says Tshuma.

“In fact, the catastrophe reignited a strong desire to do more in the protection of our wildlife heritage.”

“We are determined to use all available resources and to put our lives on the line to ensure that events of 2013 will not recur,” he adds.

Nearly 10 years after the 2013 cyanide poaching case, statistics from ZimParks show a significant decline in poaching incidents in Hwange National Park.

This has been attributed to enhanced law enforcement and demand-driven support to ZimParks from conservation partners like the International Fund for Wildlife Management (IFAW).

In fact, over the past two years, there have been zero recorded elephant poaching incidents in IFAW-supported areas of Hwange.

IFAW’s support has helped reach this milestone by focusing on the people, like Tshuma, who safeguard the region’s precious wildlife.

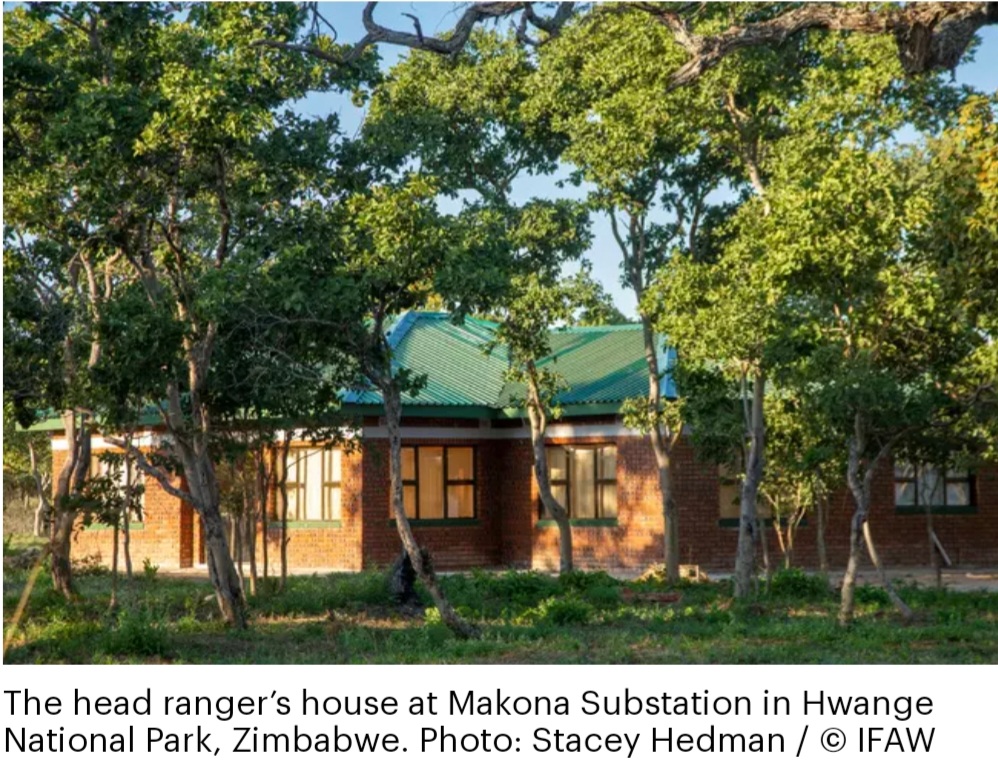

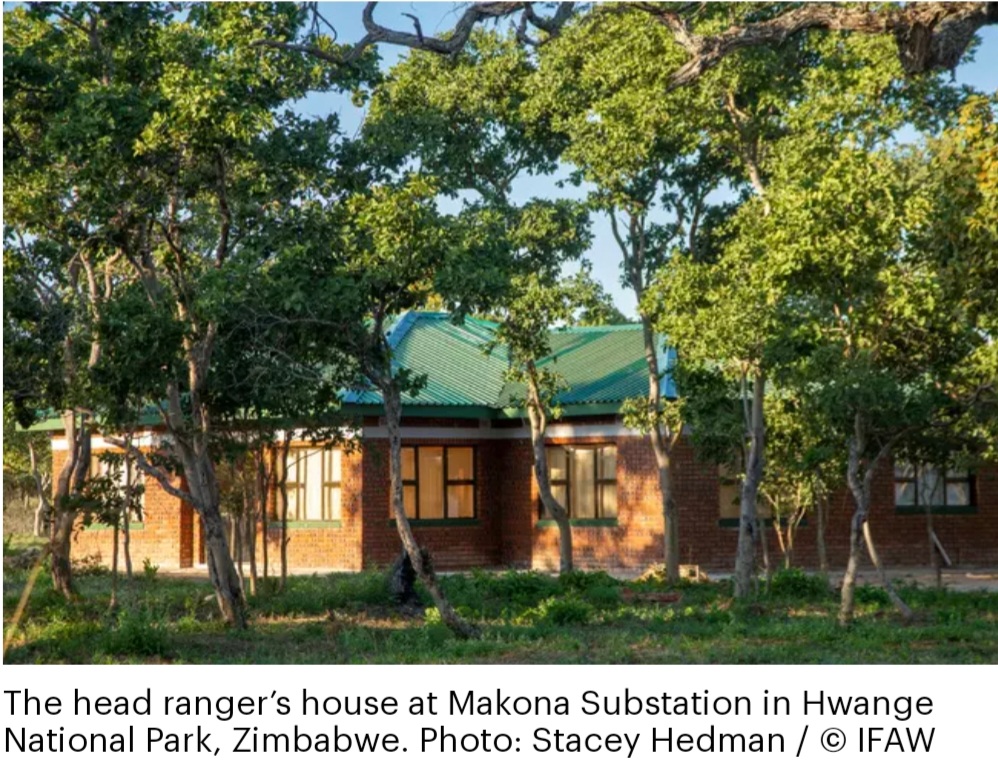

“To that end, we are improving ranger welfare by enhancing the accommodation at their base,” IFAW said.

“We’ve also provided additional patrol vehicles and refurbished the old fleet to make them more reliable and enable faster deployments.

“We continue to provide camping and field ration supplies and support training for the wildlife rangers.”

In our quest to transform the Makona area—the epicenter of the 2013 cyanide poaching incident—from a poaching hotspot to a haven for wildlife, a massive new ranger station has been established under the US$5 million five-year conservation partnership between IFAW and ZimParks. It accommodates at least 24 rangers and their families.

Tshuma is among the rangers who will call the new station home.

“We are grateful to IFAW for such an investment which will certainly help in the fight against poaching and ensure that wildlife can thrive in the Makona section of the giant park,” he says.

“I do hope that our partners will also replicate such an investment in other protected areas across the country so we can win the fight against poaching,” added Tshuma.

The infrastructure at the ranger station includes an office complex, an operations centre, a recreational facility, 12 housing units running on a renewable solar energy system, and a clean and safe water supply system.

Situated approximately 15 kilometres from the Tsholotshlo community, the new ranger station will play a key role in human-wildlife conflict mitigation.

It is also a vital part of the Room to Roam initiative, IFAW’s vision to ensure safe and healthy coexistence between people and wildlife, especially elephants, as they move freely across their natural range.

“Hwange National Park remains an important asset to the government and people of Zimbabwe.

“We must ensure that we protect wildlife and curb poaching incidents,” says Tshuma.- IFAW

Slider3 years ago

Slider3 years ago

National4 years ago

National4 years ago

Tourism and Environment4 years ago

Tourism and Environment4 years ago

Opinion4 years ago

Opinion4 years ago

Special reports4 years ago

Special reports4 years ago

National4 years ago

National4 years ago

National3 years ago

National3 years ago

National3 years ago

National3 years ago