BY RYAN TRUSCOTT

Ever thought of eating your grasshoppers with honey? Or spicy stinkbugs?

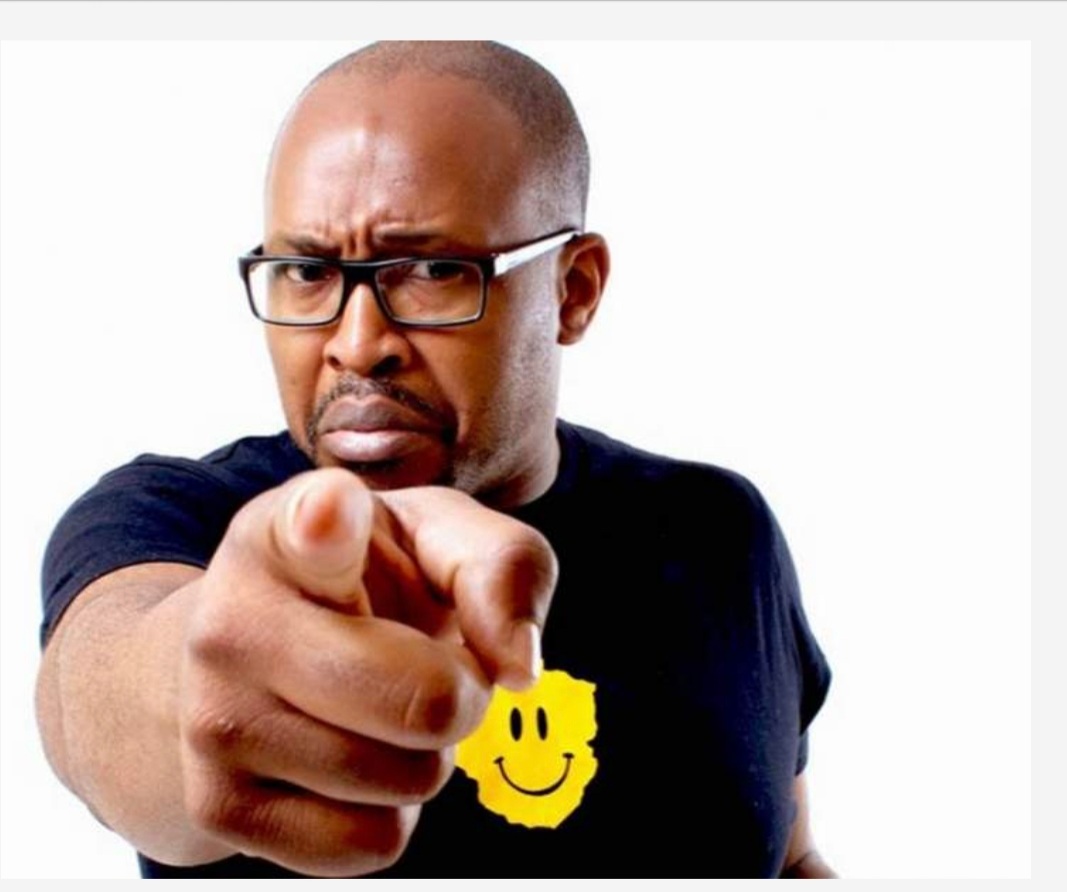

Zimbabwean comedian-turned-celebrity-chef Carl Joshua Ncube has just the recipe for you in his new e-book highlighting healthy and sustainable ways of eating.

Ncube, who moved to Victoria Falls last year to live off-grid in a converted bus with his wife Nelsy, has just brought out an e-cookbook called Chikafu — the 100 recipe diary of a Zimbabwean celebrity chef. Chikafu is the Shona word for food.

The book is being sold — sustainably — via WhatsApp to Zimbabwean customers.

His 100 recipes and pictures are a feast for the eyes on a phone screen.

But what Ncube’s really interested in is using ingredients that are at hand in rural Zimbabwe.

“I noticed that a lot of ingredients we use in Zimbabwe tend to be pests that would otherwise damage crops,” he told RFI via a zoom call from a hotel lounge during a day-trip to Victoria Falls from his village home.

Mountain of the lion

One insect featured in the recipes is the stinkbug, a small insect with a shield-like body that emits strong-smelling fluids when handled.

In some parts of Zimbabwe, including Victoria Falls, stinkbugs swarm in vast numbers ahead of the cool season looking for places to hibernate.

They can be harvested by the bagful. Once you get past their smell, they make excellent seasoning.

“The actual flavour is like a chicken or beef stock that has hardened. It’s quite fatty and crunchy on the outside,” says Ncube.

His book recommends deep frying one kilogramme of the bugs and drying them overnight.

The crucial next step is to blend them with pepper corns and cayenne pepper, according to Ncube’s recipe.

Processing insects with a blender helps people to get over the obvious psychological obstacles, he says.

“The palate adjusts to it when you add it as part of a spice blend.”

The magic ingredient in Ncube’s grasshopper and honey dish? Cottage cheese.

For Ncube, who has diabetes, the decision to start living off the grid and exploring traditional foods was a way of finding more healthy and sustainable ways of eating and living.

He and his wife converted an old bus into their home in the village of Ntabayengwe, near Victoria Falls. The village name means “mountain of the lion” and lions do occasionally pass through.

Ncube knew he was on the right track when, on his very first off-grid morning, he cooked an omelette over an open fire using free-range eggs and freshly-picked green peppers and onions.

Assault on the senses

“I’d never tasted food so fresh in my life,” he said. Once his neighbours in the village discovered there was a celebrity living in their midst, daily deliveries of fresh food began.

“People would deliver chickens to my house; they’d deliver eggs.

“Stuff was coming straight from the fields, you could still see the dirt on the vegetables.

“It was just such an incredible first week living off grid and an assault on the senses.”

Better known for his wise cracks about life in Zimbabwe and tongue-in-cheek jabs at politicians and other celebrities, Ncube says that cooking is as much a part of his DNA as comedy.

While his late father, a woodwork teacher, was a part-time comedian, his mother is a retired home economics lecturer well-versed in food and nutrition.

Zimbabwe’s rich culinary past was undervalued during the colonial years that ended with independence in 1980, said Ncube.

“What I’ve realised is that we’re not so different from a culinary perspective, globally.

“We seem to have the same things: we do broths and soups; we dry-age (meat), we hang, we cure.

“All of these processes exist but the language is different,” he explained.

He’s critical of the culinary oversimplification that saw sadza, a stiff porridge made from maize meal, declared the national staple.

Ingredients never imagined

“It was put in all our textbooks, which is not correct to do because no country in the world describes itself by one dish.”

But as much as Chikafu is about delving into the past, unearthing overlooked ways of cooking and celebrating a rich tradition, it’s also about imagining the future of Zimbabwean cuisine.

The first section of the book pays tribute to traditional ways of preparing mopane worms (an abundant moth caterpillar harvested from the leaves of mopane trees in western and south-eastern Zimbabwe), sweet potatoes and other staples.

Readers are then introduced to “ingredients used in ways they never imagined.”

This is seen, for instance, in a recipe that’s a new take on Chibuku, the popular opaque beer made from fermented maize, sorghum and barley.

He recommends mixing the brew with vanilla ice cream, chocolate milk and syrup.

Chibuku drinkers would likely be scandalised, but Ncube isn’t worried.

“I have a right as a Zimbabwean to be inventive, because whatever it is that we call tradition, was an invention at some point,” he said.

“So, I want to invent.” – Radio France Internationale

Slider3 years ago

Slider3 years ago

National4 years ago

National4 years ago

Tourism and Environment4 years ago

Tourism and Environment4 years ago

Special reports4 years ago

Special reports4 years ago

Opinion4 years ago

Opinion4 years ago

National4 years ago

National4 years ago

National3 years ago

National3 years ago

National3 years ago

National3 years ago