BY GAMUCHIRAI MASIYIWA

Binga, Zimbabwe — When Esther Musaka was a little girl, a large lorry dropped her family off in the middle of the wilderness. It was the late 1950s, and construction of Kariba Dam was underway. As the newly formed Lake Kariba — to date, the world’s largest man-made reservoir — swallowed large tracts of fertile land, it displaced an estimated 57,000 Tonga people living on both sides of the Zambezi River, including Musaka. Now 72, she remembers her parents piecing together temporary shelters of grass and branches. It took them nearly a year to settle.

Decades later, the trauma of that upheaval is being felt afresh as families in Muchesu, a village in the country’s west, brace for another displacement — this time, the result of a coal mining project. In 2010, Monaf Investments Private Ltd., a local firm, was granted a special permit for coal exploration in the region; this year, it is set to commence extraction. Mining accounts for 60% of Zimbabwe’s annual exports and contributes roughly 16% to the country’s gross domestic product; the government aims to build it into a $12 billion industry by 2023. Observers, however, warn that the rush to exploit the country’s mineral resources is leading to widespread upheaval. According to one 2019 report by a local watchdog, mining projects were slated to displace at least 30,000 families within five years.

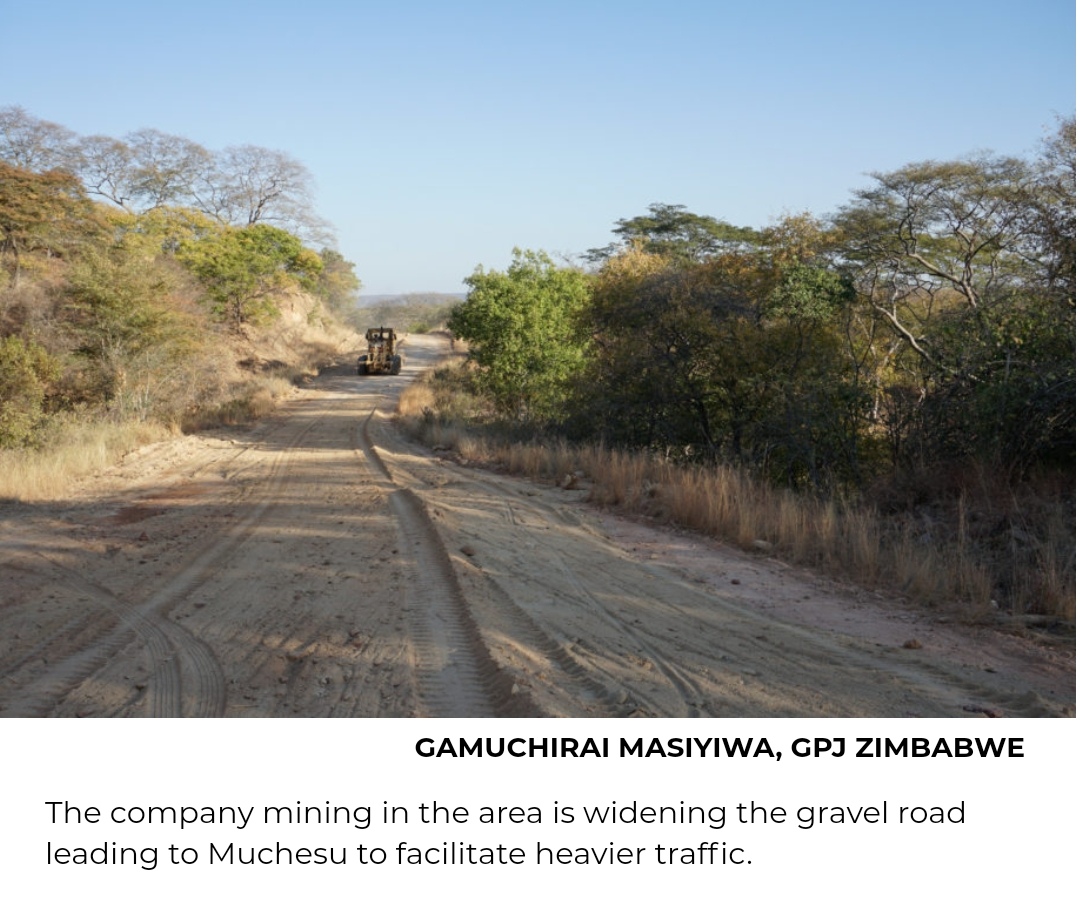

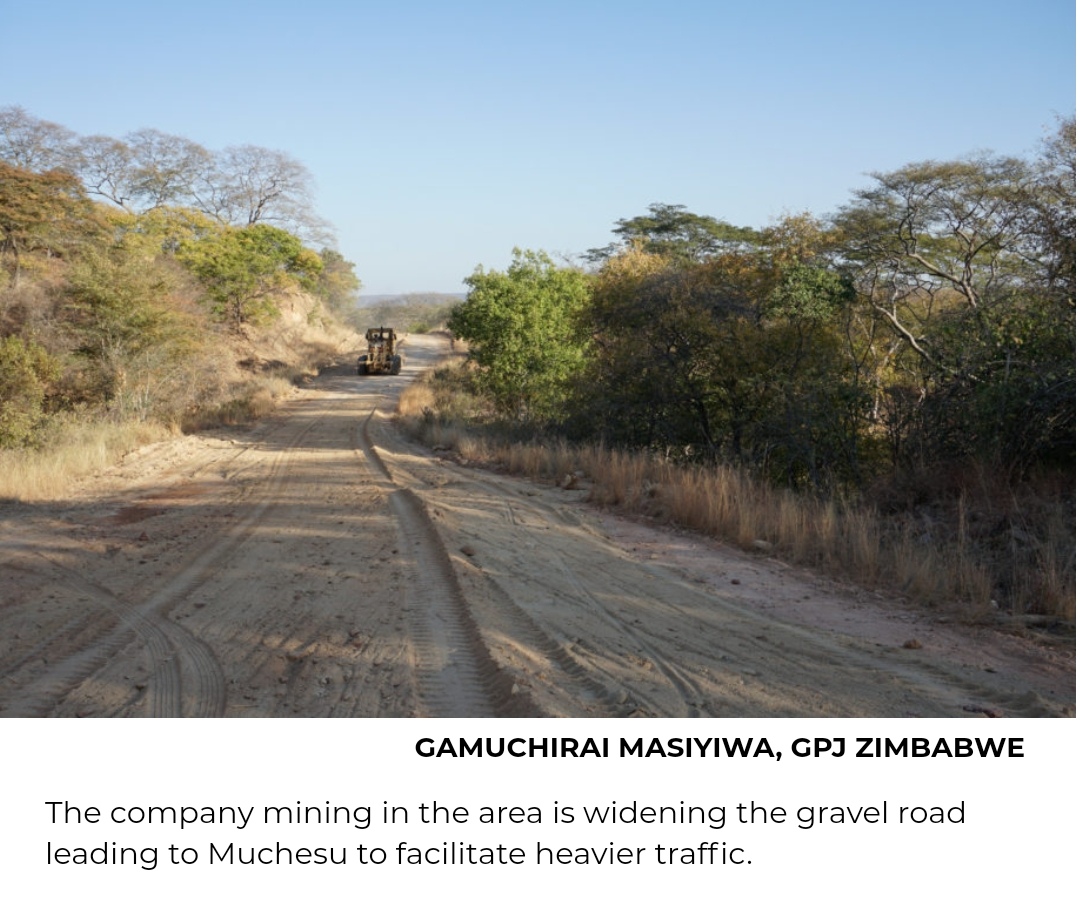

Dust engulfs the road to Muchesu, the gravel-laden trucks and bulldozers moving back and forth on it barely visible. The mining company is widening the road to facilitate heavier traffic. In Muchesu, villagers have been told not to build any new structures. Thirty-eight families are slated for relocation in the first phase of the project, says local councilor Mathias Mwinde. Another 105 will be displaced in the second phase. No one knows for certain where they will be relocated.

At her age, Musaka is racked with anxiety at the prospect of starting anew. “Who will clear the land for me?” she asks sorrowfully, smoking a gourd pipe outside her home. “I am no longer fit to do all that.”

Nothando Mugande Mudimba, 37, was born in Muchesu. When her grandparents settled here decades ago, they struggled with wild animals for years, and she worries she will have to, too. “It will be hard to safeguard our livestock if we are moved to the mountainous area that we suspect they will take us to, because there are hyenas, elephants and lions in those forests,” she says. “I have three cows, five goats and more than 20 chickens, which can become meals for the wild animals there. We want them to ensure that we are well protected before they move us and ensure we have access to water, fencing and roads, clinics and schools.”

Village headman Wilson Munkombwe Siamulafu I, 71, worries about ready access to water. Like many others, he grows tomatoes, cabbage and rapeseed to sell locally. His grandparents used to live in Muchesu, he says, and were chased away during the colonial era — only to return in the 1950s, when the construction of Kariba Dam displaced them. “My parents said that they walked to this place because they knew it had fertile soil,” he says. “Others were brought later, by trucks.”

A tall, slim man who squints when he speaks, Munkombwe can’t help but feel helpless. “I have nothing that I can do or say because they have already chased us,” he says. “We will only follow what they say.”

Shadreck Mwinde, 64, has already begun to feel the effects of the project. In 2020, the mine subsumed his field. The company promised him 1 ton of maize each year until the households were relocated. “I was given 1 ton last year in February,” he says, “and this year nothing has come.” (Monaf Investments did not respond to requests for comment.) This season, he cultivated a borrowed piece of land — but it yielded only four 50-kilogram (110-pound) bags of maize, not nearly enough to sustain his family of 14 children, 10 of whom live with him and his wife. He has already sold a cow to cover their schooling costs.

Earlier this year, in March, construction workers drilled two holes near his house, destroying some trees in his compound. The holes were left uncovered for a week, Mwinde says, and treated with chemicals; when it rained the holes filled with water. “Four of my goats died,” he says. “I do not know if it was because of those chemicals.” In late June, about 50 meters (164 feet) away from his house, there was a large open hole, 9 meters (30 feet) deep, guarded by security personnel. “Even though someone is manning this place, the hole is dangerous for both our children and animals,” Mwinde says, pointing toward it.

Alarmed by the rising trend in mining-induced displacements, a coalition of nongovernmental organizations collectively called Publish What You Pay has petitioned the Zimbabwean government to protect the rights of the affected. “In Zimbabwe, mining companies often fail to pay adequate and prompt compensation, give people adequate notice and follow due process before relocation,” its petition notes, adding that any project that necessitates displacement must require the unreserved consent of affected communities, relocation with prompt and fair compensation, resource sharing and adherence to international best practices.

Effort Nkazimulo Dube, a fellow at the Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association, says mining-induced displacement is a growing trend. “But it’s not widely talked about, especially when communities are not coming up to report the matter,” he says, noting that there have been cases in which people who oppose mining projects are singled out. “I am not aware of any laws that prohibit double displacement,” he adds. “Mining is given a top priority in our laws, so if minerals are discovered where people live, there is a possibility of being displaced again.”

Mathias Mwinde says, “The eviction happening now is better than what happened in the 1950s. We agreed that no one will be moved before houses are built, there is access to water and affected people are given first preference for employment.” But he notes that Monaf Investments has not been clear on how much monetary compensation each family will receive. Meanwhile, Richard Moyo, state minister for provincial affairs and devolution in Matabeleland North, says the villagers are not being evicted — rather, it is “rural organization for rural development.” He adds that “intensive and extensive consultations are carried out to allow buy-in of the community.”

“Government, under new dispensation, respects property rights and upholds constitutionalism,” he says, “hence the concerns of the affected community are taken on board with a view to make whatever investment to give that community a better livelihood.” Indeed, the new development pleases some in Muchesu. Chitondezyo Murisaka, 31 and a father of one, has worked at the mine for the past five months and earns a daily wage of $7. “Because of the job, I have managed to pay part of my lobola [a bride price paid by the husband to the wife’s family] for my wife,” he says.

But Musaka and Mudimba worry that what will be lost can never be compensated. “My children’s ancestral spirits are here,” says Mudimba. “Sometimes when a child gets sick, prophets and traditional healers tell you to visit the graves and do certain things for the child to heal.” Musaka says many of her relatives were buried along the Zambezi where her family used to live. “Their graves were covered by the river, and we have no trace of them anymore. This is what is going to happen again,” she says. In her old age, her one wish is to be buried beside her husband. “If I am moved, that will not happen.”- Global Press

Slider1 year ago

Slider1 year ago

News1 year ago

News1 year ago

Tourism and Environment2 years ago

Tourism and Environment2 years ago

News3 years ago

News3 years ago

News2 years ago

News2 years ago

News2 years ago

News2 years ago

News1 year ago

News1 year ago

News2 years ago

News2 years ago