Slider

New rhino sanctuary changes face of Tsholotsho communities

Published

3 years agoon

By

VicFallsLive

BY TERRY WARD

To walk among rhinos is no subtle thing.

The animals themselves are, after all, enormous, with males tipping the scales at over 5,000 pounds and females typically punching around the 3,700-pound mark.

To watch them stop to pick up your scent and sounds when they can’t yet quite see you in the distance, their ears swivelling like satellite dishes, can make your heart thunder in your ribs.

But it was the measured deliberateness in the manner of two white rhinos moving through their new territory at the edge of Hwange National Park — Zimbabwe’s largest national park, from which the species was poached to disappearance sometime in the early 2000s — that struck me most as I plodded within meters of the magnificent Thuza and Kusasa at the Imvelo Ngamo Wildlife Sanctuary.

Then, once I regained my composure somewhat from the rush of it all, the surprise was that these animals are even here at all.

The newly established preserve for the two male white rhinos, set on communal land formerly used as important grazing grounds by livestock owners from neighboring villages in the Tsholotsho district, is at the heart of the Community Rhino Conservation Initiative (CRCI).

It’s a landmark conservation project in a country often overlooked as a safari destination in favour of neighbouring South Africa and Botswana.

And it’s the people who live in the areas bordering the park who are now charged with protecting Thuza and Kusasa.

The two bulls are the first animals to occupy what the CRCI hopes will eventually be a string of sanctuaries lining the park’s boundaries (with the eventual goal of someday safely reintroducing the animals into the 5,657-square-mile park itself).

In May of this year, after years of preparation, much of which took place during the throes of the pandemic, the animals (donated by a private reserve, Malilangwe, in south-eastern Zimbabwe) were translocated by road some 500 miles across the country to communal land that has been turned into a reserve for the purpose of protecting the rhinos.

And now, tourists can visit the rhinos at the CRCI and walk alongside them, protected by villagers paid to guard the animals.

| The CRCI represents a milestone for conservation in Zimbabwe because it’s the first attempt to house rhinos on community land in the country, says Bruce Clegg, a senior ecologist with the Malilangwe Turst who is also a member of Zimbabwe’s National Rhino Committee (part of ZimParks, the country’s Parks and Wildlife Management Authority).

“If successful, the project may act as a catalyst for similar initiatives and, in so doing, help to foster an improved relationship between people and wildlife,” Clegg says. Advertisement

“Africa is littered with failed community wildlife projects because they have been forced down a community’s throats and later rejected,” says Zimbabwean Mark Butcher, a former national parks ranger and managing director of Imvelo Safari Lodges, a key partner in the initiative. He remembers when white rhinos roamed free in the Hwange’s southern grassy lands, and when the last one was poached away from it too (there are still a handful of black rhinos in the park’s remote northern reaches, Butcher says, but they are rarely seen). And he’s dreamed of seeing white rhinos back in Hwange since. But while conserving and preserving for future generations is a “wonderful concept,” Butcher says, it’s one that is a luxury to many people in Africa who are starving or just trying to find the money to pay school fees for their children’s education. Advertisement

“Particularly people living around the parks in Africa can’t afford that luxury [of a Western mindset toward conservation],” he says. But Butcher is convinced the way to turn communities into conservationists is straightforward. “It’s about creating jobs and socioeconomic developments so the cost of poaching is higher than the cost of protection,” he says. Advertisement

To that end, the CRCI spent the pandemic training roughly 30 men from the local villages to be scouts. They are the brawn and brains behind the Cobras Community Wildlife Protection Unit (called the COBRAS). The unit not only closely guards Thusa and Kusasa around the clock on foot patrols and from observation towers, but is also on call to help people from nearby villages address problem animals — such as elephants trampling a crop of watermelons or lions menacing a farmer’s cattle. Female villagers are being recruited to the CRCI to work on intelligence and surveillance efforts related to anti-poaching too. Advertisement

“People don’t have bank accounts here, they have cattle,” Butcher says. And using communal land as a guarded wildlife sanctuary also serves as a buffer between the people living in the villages and the wild animals living in the national park that often menace them and their livelihoods. |

Funds raised from tourists visiting the CRCI — where it’s possible to enter the land inside the sanctuary’s electrified gates to walk alongside the rhinos while listening to the stories of the COBRAS, some of whom were former poachers themselves — go directly toward community improvements to schools, boreholes and healthcare facilities.

Visitors currently pay a US$180 optional fee to walk with the rhinos, but next year a US$100 per person rhino conservation fee will be applied to all guests at Imvelo’s four safari lodges.

The revenue raised is already being used to fund operating expenses and nurses salaries at a new clinic in nearby Ngamo, in addition to supporting the rhino cause.

For 26-year-old COBRA Wisdom Mdlongwa, the rewards of helping protect these animals — that he is also seeing for the first time in his life here in his home region — are already becoming clear.

The COBRAS are celebrated as local heroes in their home villages, where kids play COBRAS in the sandy streets in the same way others around the world might play cops and robbers.

“I didn’t grow up seeing rhino,” Mdlongwa says.

“But now, in addition to tourists, local people also get the chance to come here and see them.”

And witnessing the impact on the local schoolchildren who visit the COBRAS and CRCI to see the rhinos has given him hope that in the future the village’s younger children will want to earn their livelihoods and provide for their families working to protect the animals.

“Once we have money from this project, it helps support our community in many ways,” he says.

Visitors who come to visit the rhinos and meet the COBRAS are usually staying at Imvelo’s Camelthorn Lodge, on a plot of communal land adjacent to the sanctuary.

One of Imvelo’s four safari lodges in and around Hwange National Park, the eight-villa property first opened its doors in 2014 and is managed by two women from neighboring Ngamo village.

Before construction began, the late village chief of Ngamo, Chief Mathuphula, was adamant that instead of building the lodge in the typical fashion of luxury canvas safari camps across Africa, it should be constructed in a permanent fashion, with the main lodge and accompanying guest accommodations made from concrete and stone instead of canvas.

That way, Camelthorn would stand the test of time for future generations — whether it would continue to operate as a tourist lodge in the future or not.

“The whole community is very proud of what has been achieved and what our local people have done with the building of Camelthorn Lodge,” says Johnson Ncube, the current Ngamo line village headman.

“I know that with this kind of lodge built out of concrete, it is going to remain standing for quite a long time, whereby even the coming generation will be able to enjoy it.”

“And I know one day, even if Imvelo is gone, this structure will remain standing for us where the community can run it as a lodge for more years and to benefit coming generations,” he says.

It is a sentiment that Butcher of Imvelo Safari Lodges wholly supports.

“The reality is that the long-term future of Africa’s wildlife will be decided by the rural communities that live with that wildlife,” he says.

Butcher says there are plans to open a second, larger sanctuary in 2023 on neighbouring communal land, with the selection and training for new COBRAS scheduled to start this November.

And in working to bring rhinos back to the border of Hwange National Park and onto community lands with CRCI, he says he is hanging his entire reputation on the concept of community-based conservation.

Afterall, Thuza and Kusasa — who were dehorned to protect them in transit as well as to make the animals less attractive to poachers — still face an ongoing poaching threat.

Butcher acknowledges it’s only a matter of time before there’s an attempted strike on the animals (the COBRAS are taught to shoot to kill any potential poacher).

But as long as the animals remain protected, the risks will be worth the reward.

“I strongly believe we have a moral obligation to ensure that the communities that live next door to wildlife and protect it — these communities that bear the consequences of living next door to the lions and elephants and rhinos, and what that means for their agriculture and families and their own livelihoods — that they are the ones that get the benefits from the wildlife and tourism benefits that derive from conservation.”

“The only way wildlife and wild places in Africa can survive is with the support of the communities that live around those protected areas and wildlife,” Butcher says.

“That’s why people need to come on safari, it’s critical to conservation.”

OZY

You may like

Slider

From discarded glass to second chances: How conservation is rebuilding the lives of Zambia’s street boys

Published

2 days agoon

January 19, 2026By

VicFallsLive

BY NOKUTHABA DLAMINI

Livingstone, Zambia — In Maloni township, the sound of glass snapping cleanly against a cutter echoes through the yard of a modest home. What was once a discarded beer bottle now sits neatly trimmed, smoothed into a drinking glass. For a group of young men long dismissed as “junkies,” this simple act has become the beginning of a second chance.

At the centre of this transformation is Songiso Mukena, a conservationist, tourism practitioner and founder of the Responsible Earth Keepers Foundation (REK). Through conservation work, recycling, football and mentorship, Mukena is quietly rewriting the futures of boys once written off by their own communities.

“My name is Songiso Mukena from Livingstone, Zambia,” he says. “I am the founder of Responsible Earth Keepers Foundation – a non-profit making organisation.”

A journey rooted in hospitality and conservation

Mukena’s passion for conservation grew out of more than 15 years working in Zambia’s hospitality industry. While employed at Jolly Boys Backpackers in Livingstone, he was involved in a programme focused on responsible tourism and waste management.

“For me, it was just work,” he explains. “It was all about waste separation, finding a better place where to take or whom to give. We were doing worm farming and also just learning how to manage waste.”

That experience sparked a deeper interest. “I think it’s one of the places I worked that really opened my mind,” he says.

In 2016, a visit to a recycling organisation became a defining moment.

“I was amazed with what I saw,” Mukena recalls. “They were giving life back to bottles that were discarded out there or thrown out. They would cut them, make candle holders, lanterns and drinking glasses.”

Although he wasn’t taught the technique, the idea stayed with him. “I started doing research on how to cut a bottle and make a drinking glass,” he says. “It wasn’t easy.”

A breakthrough came when former employers, Mr and Mrs Sikaneta of Munga Eco-Lodge, donated a glass cutter.

“I started practicing and practicing,” Mukena says. “The whole of 2017 I was practicing. In 2018, I started taking bottles to my house and cutting them.”

Soon, people began buying the glasses.

“For me, my mind shifted,” he says. “I thought, I think this can be a big idea on recycling.”

COVID-19 and a move into the community

The COVID-19 pandemic forced Mukena out of employment as tourism ground to a halt. He moved from Linda township to his own plot in Maloni, an area facing deep social challenges.

“It’s a remote area,” he explains. “It’s one of the places where you find early pregnancies, boys failing exams and turning into what today are called junkies.”

Many of these boys had gone through traditional initiation ceremonies, after which they were often stigmatised.

“When they come back, the community views them in a different way,” Mukena says. “Once you go there and come back, you are not taken as a normal boy child.”

Instead of distancing himself, Mukena opened his space to them.

“I started teaching those boys how to cut bottles, making drinking glasses,” he says. “We started with about ten boys.”

The glasses were sold, and the money shared according to need.

“If one lacked shoes, we would sponsor that,” Mukena explains. “If another boy wanted to go back to school and lacked books, we helped.”

Healing beyond skills

The transformation was not just physical or financial. Mukena’s wife, Yvonne, a psychosocial counsellor, joined the initiative.

“She started talking to the boys,” he says. “Trying to get their minds shifted.”

Their home became a safe space.

“Our home became a home of many,” Mukena says. “Some kids would come just to play.”

Recycling soon funded broader social causes.

“We said, how about we sell these glasses back into the charity to help make it self-sustainable? Mukena explains. “Waste management became a starting point for other projects.”

Football as a tool for dignity

Football emerged naturally from the boys themselves.

“They were already playing – and with real talent,” Mukena says. “One day they came and said, ‘Father, we want to play City Stars and we’ll win!”’ City Stars is a professional team.

Recognising their talent and passion, the boys asked for support.

“They said, if possible, can you organise football kits for us?” he recalls.

A local church donated land for a pitch, and REK FC was formed. Recycling income helped support the charity’s activities, linking conservation directly to sport.

Football also brought structure, discipline and confidence.

“We don’t just concentrate on soccer,” he says. “We also give motivational talks, encouragements, testimonies and Bible readings. At the end of the day, it’s a mind change that we are looking for.”

Support from abroad, built on trust and friendship

Among those drawn to support Mukena’s work were two tourists from the UK, Simon Greene and Audrey Furnell. Simon explains why grassroots initiatives resonate with donors today:

“In return for a relatively modest donation anyone can make a tangible difference. Supporters like us can see a direct return on what we give which is incredibly rewarding.”

Simon says this is exactly the kind of work they want to promote.

“We’ve learnt a huge amount from Song and Yvonne and were struck by their kindness and impressed by their drive to do more for his community,” Simon says.

Their family’s support began with a classroom project in Linda, expanded to monthly assistance for school needs, and later funded a borehole near Kazungula.

When introduced to the boys of Maloni, Audrey says:

“We saw their passion for football and it was clear they deserved the chance to be their best on the field – but without proper kit that could never happen.”

Soon afterwards, Simon recalls:

“Songiso lost no time, organised all the kit and immediately arranged a match on Christmas Eve with REK FC playing against a professional team. We were thrilled.”

Rewriting the story of the boy child

Mukena believes the project addresses a wider national issue.

“There was a campaign for educating the girl child,” he says. “That campaign was done very thoroughly. But the boy child was left behind.”

He believes that neglect has contributed to rising numbers of boys labelled as criminals and drug users.

“When a boy’s mind is changed,” Mukena says, “it’s an achievement for the organisation, the community and the country.”

Today, REK works with approximately 100 boys aged between 15 and 22, with about 25 actively involved in recycling and football.

The long-term goal is to establish a recycling and skills training centre employing youth from the community.

“We want a better community,” Mukena says.

Small acts, lasting change

In Maloni, discarded bottles are no longer just waste. They are tools of transformation — funding education, restoring dignity and giving young men a reason to believe in themselves.

For Mukena, success is simple.

“One day we hope a boy will be picked to play for a professional team,” he says, “that will be an incredible achievement for him — and for us.”

And for Simon and Audrey:

“We feel blessed to have Songiso in our lives. Being able to see REK make valuable improvements like these is very rewarding. We’d like more people in the wider donor community to act as we have – together we can make a difference.”

Slider

Human-wildlife conflict in Zimbabwe is a crisis: who is in danger, where and why?

Published

5 days agoon

January 16, 2026By

VicFallsLive

BY BLESSING KAVHU

In the fishing villages along Lake Kariba in northern Zimbabwe, near the border with Zambia, everyday routines that should be ordinary – like collecting water, walking to the fields or casting a fishing net – now carry a quiet, ever-present fear. A new national analysis shows that human-wildlife conflict in rural Zimbabwe has intensified to the point where it has become a public safety crisis, rather than simply an environmental challenge.

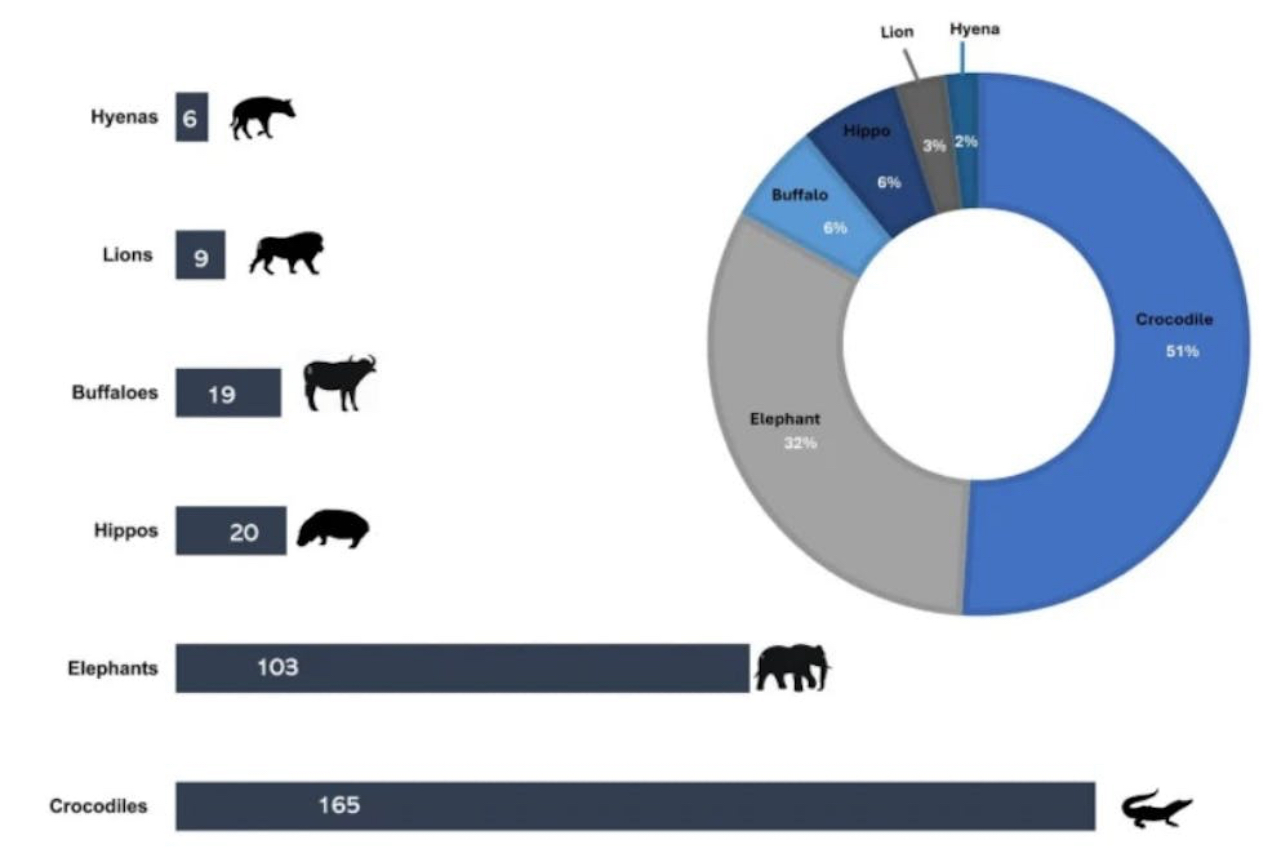

Between 2016 and 2022, 322 people died in wildlife encounters. Annual fatalities climbed from 17 to 67: a fourfold increase in just seven years. These fatal encounters are concentrated in communities that live closest to protected areas and water bodies. Here, people and wildlife compete for space and survival.

Protected areas and rivers provide water, forage and shelter for wildlife. Rural households rely on the same landscapes for farming, fishing and domestic water. The study shows that this overlap between human activity and wildlife movement sharply increases the risk of fatal encounters.

Historically, human-wildlife conflict research and policy in southern Africa focused on economic losses such as destroyed crops, livestock predationand damaged infrastructure. Fatal attacks on people were often treated as rare or incidental. This study shifts that perspective by showing that human deaths are not isolated events, but a growing and measurable pattern that demands urgent attention.

I am a US-based Zimbabwean scientist working with Zimbabwean conservationists. We analysed national wildlife-related fatality records from the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority. The central questions were: how many people are dying from wildlife encounters, where are these deaths occurring and which species are responsible?

The findings were stark. Fatal encounters are rising rapidly, are geographically clustered in the north and western districts, and are driven primarily by two species: crocodiles and elephants (not lions, as people might expect). The implications extend beyond conservation to include trauma, fear, retaliatory killings of wildlife and the need for targeted, locally specific interventions.

Patterns in the data

The study reveals that more than 80% of recorded deaths involved only two species, elephants and crocodiles. Crocodiles alone were responsible for slightly more than half of all fatalities. Many of these incidents happened during activities people cannot avoid: fishing, crossing rivers, bathing, or washing clothes in rivers and lakes. These encounters are sudden and often impossible to anticipate, especially in places where visibility is poor and safe water access is limited.

Elephants were responsible for nearly a third of the deaths. These happened mainly during crop-raiding incidents or when communities attempted to chase elephants from fields and homesteads, or when people were walking to school and work. These confrontations often occur at night or in the early morning when visibility is low. Lions, hyenas, hippos and buffalo contributed only 17% of fatal incidents during the study period.

The rise in lethal encounters appears to be driven by several overlapping forces. Zimbabwe still holds one of Africa’s largest elephant populations, estimated at over 80,000 animals. This is second only to Botswana. In dry years elephants move over long distances in search of water and forage, increasing their presence in communal lands. Shrinking natural habitats and growing rural populations mean that human populations are expanding into wildlife corridors. Climate change, particularly recurring droughts, intensifies the competition for water and space.

The geography of the fatalities reveals a clear pattern. Most deaths occurred in Kariba, Binga and Hwange. These are districts along the country’s northern and western frontier, with a combined population of about 343,264 people. They have large water bodies that support abundant crocodile populations; they are close to protected areas with high elephant numbers; and people there depend heavily on farming, fishing and natural resource use.

How people feel

These encounters leave people with fear. Parents become anxious about children walking to school, farmers worry about tending crops at dawn and communities may avoid crossing rivers.

But people aren’t getting mental health support. So grief and fear can turn into anger, often resulting in killings of wildlife. A destructive cycle undermines conservation and damages trust between communities and authorities.

What to do about it

Different places face different dangers, and solutions should reflect that.

Areas near crocodile-prone rivers need safe water access and crossing points and redesigned community washing areas. Districts where elephants are responsible for most fatalities require better early-warning systems, community-based monitoring networks and low-cost methods to deter elephants from crop fields. These measures must be paired with community education and consistent follow-up support.

The findings highlight that coexistence will not be possible without recognising the emotional and psychological dimensions of living alongside wildlife. The responsibility lies with government agencies working with communities. These must be supported by conservation organisations and health services. Counselling, community healing processes and long-term engagement can help break the retaliatory cycle.

Research from other African settings shows that targeted solutions grounded in community involvement and local risk patterns are key to reducing conflicts. In northern Kenya, community-based early warning systems that alert villagers to elephant movements have significantly reduced fatal encounters. Beehive fences and chili-based barriers have helped protect crops without harming wildlife.

In Uganda’s Murchison Falls area, surveys found that local people preferred physical exclusion measures and the relocation of specific crocodiles as ways to lower the risk of attacks. In South Sudan’s Sudd wetlands, communities identified crocodile sanctuaries as one way to reduce dangerous interactions. In Zambia’s lower Zambezi valley, villagers highlighted the need for more alternative water access points (such as boreholes).

These examples show that fatal encounters are not inevitable. When interventions are matched to the species involved and the daily realities of local communities, both human deaths and retaliatory killings of wildlife can be reduced.

Zimbabwe’s wildlife remains a source of national pride and a cornerstone of tourism. But conservation cannot succeed if the people who live closest to wildlife feel unprotected or unheard. A future where people and wildlife thrive together depends on acknowledging that human wellbeing is inseparable from the wellbeing of the ecosystems they share.

SOURCE: THE CONVERSATION

BY RHETT AYERS BUTLER

SUMMARY:

- A recent Nature paper argues that many persistent failures in conservation cannot be understood without examining how race, power, and historical exclusion continue to shape the field’s institutions and practices.

- The authors contend that conservation’s colonial origins still influence who holds decision-making authority, whose knowledge is valued, and who bears the social costs of environmental protection today.

- As governments pursue ambitious global targets to expand protected areas, the paper warns that conservation efforts risk repeating past injustices if Indigenous and local land rights are not recognized and upheld.

- To address these challenges, the authors propose a framework centered on rights, agency, accountability, and education, emphasizing that more equitable conservation is also more durable.

Conservation often presents itself as a technical enterprise: how much land to protect, which species to prioritize, what policies deliver results. A recent paper in Nature argues that this framing misses something fundamental. Many of the field’s most persistent failures, the authors contend, cannot be understood without confronting how race, power, and historical exclusion continue to shape conservation practice today.

The paper, A Framework for Addressing Racial and Related Inequities in Conservation, does not claim that conservation is uniquely flawed, nor that injustice is universal across all projects. Its argument is narrower and more pointed. Modern conservation, it says, emerged from a colonial context that treated land as empty and people as obstacles. Those assumptions were never fully dismantled. They survive in subtler forms, influencing whose knowledge counts, who bears the costs of protection, and who decides what success looks like.

The authors, led by Moreangels Mbizah of Wildlife Conservation Action in Zimbabwe, trace conservation’s institutional roots to the late nineteenth century, when protected areas were established across colonized landscapes through forced removals and restrictions on customary land use. Indigenous peoples and rural communities were often excluded in the name of preserving “pristine” nature. Although conservation has evolved since then, the paper argues that these early patterns still shape present-day practice through what it calls “path dependencies”: inherited norms that continue to privilege outside expertise and centralized control.

One consequence, according to the authors, is the persistent marginalization of Indigenous peoples and local communities, particularly in the Global South. These groups are frequently described as “stakeholders” or “beneficiaries” rather than rights-holders with authority over their lands. The language may sound neutral, the paper suggests, but it often masks unequal power relationships. Even well-intentioned projects can reproduce older hierarchies if communities are consulted only after priorities are set, or if participation is limited to implementation rather than decision-making.

The paper pays particular attention to the current push to expand protected areas to cover 30% of the planet by 2030. In principle, the authors argue, this target could support more pluralistic forms of conservation, including Indigenous-managed territories and community conservancies. In practice, they warn, countries lacking legal mechanisms to recognize customary land rights may default to state-led models that repeat earlier injustices. Conservation success, measured narrowly through ecological indicators, can come at high social cost when human rights are treated as secondary concerns.

The paper pays particular attention to the current push to expand protected areas to cover 30% of the planet by 2030. In principle, the authors argue, this target could support more pluralistic forms of conservation, including Indigenous-managed territories and community conservancies. In practice, they warn, countries lacking legal mechanisms to recognize customary land rights may default to state-led models that repeat earlier injustices. Conservation success, measured narrowly through ecological indicators, can come at high social cost when human rights are treated as secondary concerns.

Another theme the authors examine is the way conservation narratives value animals and people. Campaigns aimed at audiences in Europe and North America often focus on the moral worth of individual animals, sometimes in ways that implicitly devalue the lives of people who live alongside wildlife. When human–wildlife conflict results in injury or death, local suffering may receive little attention, while the killing of a charismatic animal can provoke global outrage. The authors argue that such asymmetries are not incidental; they reflect deeper processes of “othering” that shape whose lives are seen as grievable or deserving of protection.

The paper is careful not to frame these dynamics as purely racial in a narrow sense. Instead, it emphasizes intersections of race, class, geography, and political power. Urban elites in low-income countries, the authors note, may exercise authority over rural communities in ways that mirror global North–South inequalities. Conservation led by local actors is not automatically just. What matters is how power is distributed and whether affected communities retain meaningful agency.

To address these patterns, the authors propose what they call the RACE framework: Rights, Agency, Challenge, and Education. The framework is not presented as a checklist or a universal solution. Rather, it is intended as a lens through which conservation organizations, researchers, and funders might examine their own practices.

Rights, in this framing, are foundational. The paper argues that conservation cannot be sustainable if it undermines basic human rights, including rights to land, culture, and self-determination. Agency follows from this: communities must have real authority over decisions that affect their territories, not merely advisory roles. Challenge refers to the obligation, particularly among powerful institutions and individuals, to speak out when conservation practices cause harm or exclusion. Education, finally, involves confronting conservation’s own history and recognizing knowledge systems that exist outside Western scientific traditions.

The authors stress that this is not about revisiting past wrongs for their own sake. Understanding history, they argue, is necessary to avoid repeating it under new banners. Nor is the framework framed as an attack on conservation itself. On the contrary, the paper insists that conservation outcomes are likely to be stronger when communities closest to the land are recognized as stewards rather than obstacles.

There is a pragmatic strand running through the analysis. Conservation, the authors note, increasingly operates in a politically fragmented world, with declining public funding and growing skepticism toward international institutions. Projects that lack local legitimacy are more vulnerable to conflict and reversal. Addressing inequities, in this sense, is not only an ethical concern but also a strategic one.

The paper does not pretend that change will be easy. Power, once accumulated, is rarely surrendered voluntarily. Nor does it suggest that conservation can resolve broader social injustices on its own. Its claim is more modest, and perhaps more demanding: that conservation must stop treating inequality as an external issue and recognize how deeply it is woven into the field’s own structures.

For a discipline accustomed to measuring success in hectares and population counts, this is an uncomfortable proposition. But the authors’ central point is straightforward. Conservation is about relationships—between people and nature, and among people themselves. Ignoring those relationships does not make them disappear. It only ensures that their consequences are felt later, often by those with the least power to absorb them.

SOURCE: MONGABAY

Trending

-

Slider3 years ago

Slider3 years agoInnscor launches brewery to produce Nyathi beer

-

National4 years ago

National4 years agoIn perched rural Matabeleland North, renewable energy is vital

-

Tourism and Environment4 years ago

Tourism and Environment4 years agoStrive Masiyiwa’s daughter opens luxury Victoria Falls lodge

-

Opinion4 years ago

Opinion4 years agoA street art mural in Zimbabwe exposes a divided society

-

Special reports4 years ago

Special reports4 years agoTinashe Mugabe’s DNA show’s popularity soars, causes discomfort for some

-

National4 years ago

National4 years agoVictoria Falls’ pilot dies in helicopter crash

-

National3 years ago

National3 years agoCommission of inquiry findings fail to be tabled as Victoria Falls councillors fight

-

National3 years ago

National3 years agoHwange coal miner fires workers over salary dispute