BY NOKUTHABA DLAMINI

Two months ago, cervical cancer claimed the life of her sister.

Now, 41-year-old Olidah Ngulube, is battling breast cancer, bed-ridden at her late sister’s home in the Singwangombe village of Nkayi in Matabeleland North province.

In Victoria Falls, 51-year-old Mildred Mhlanga, is battling the same disease, which has resulted in her being diagnosed with a severe heart problem after undergoing successful chemotherapy as the cancer had reached stage four of the deadly disease, being the advanced stage.

“I hardly sleep at night as the pain sharpens and l often cry with very little help as my family does not know how to assist me,” says a visibly anguished Ngulube.

Ngulube has not been able to go to Mpilo Central Hospital in Bulawayo where she was referred to by Nkayi nurses for her to be examined by a specialist.

She fears that just like her sister who succumbed to the same disease, and with the collapsing health system in the country coupled with prolonged lockdowns to slow down the spread of Covid-19, her chances of survival are slowly becoming slim.

Ngulube said: ” I started feeling some lumps and severe pains on my left breast when my sister died, but at hospital they told me that for me to be able to be treated, I will need money in United States dollars for the first tablets, consultation, and examination before the chemotherapy process on top of transport money to Bulawayo. I don’t have it and that’s why l am in this anguish. I don’t have money for treatment.”

Breast cancer has become Zimbabwe’s new health headache, and it is not alone, having teamed up with cervical cancer, becoming the poor country’s tense disease in the health sector.

“I’m in pain, dying is better, I wait for my day to rest from this pain,” fragile and visibly thin Mhlanga said as she winced in pain, lying in bed in her room while her eyes were watery.

For any cancer patient like Mhlanga, what decides the treatment depends on the stage of the cancer

For her, even though she successfully finished her three-year-long chemotherapy in February this year, she had had to face yet another severe disease being the side effects of the treatment process.

“I was supposed to go for my right breast removal, but I’ll not be able to do so because I am now on a new treatment for a heart problem,”

“When I visited the doctors in Bulawayo, they told me that those are side effects of chemotherapy so I’m now on twin medications that l need to purchase at US$30 each per month.”

Battles on two fronts

Statistics from the Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVac) 2021 Rural Livelihoods Committee Assessment Report revealed a shocking pattern about the high disease burden in Matabeleland North province.

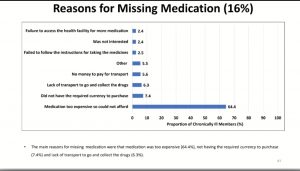

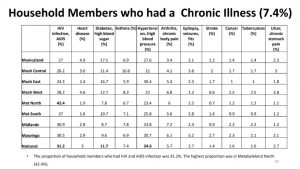

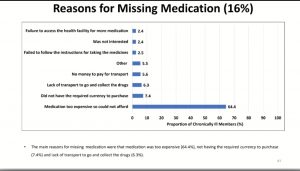

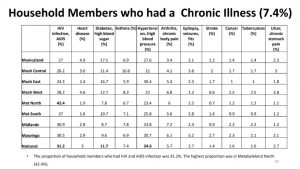

For example, the province has the highest proportion of household members with HIV/Aids at 42.4 percent against a national average of 3.2 percent. The province also has some of the highest percentages of people with chronic illnesses that are missing their medication.

In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the number of annual cancer deaths globally reached at 8.2 million, adding that the numbers were expected to triple by 2030.

With breast and cervical cancers as the country’s twin evils haunting hundreds of women like Ngulube and Mhlanga, the Health and Child Care ministry says approximately 1 500 women are succumbing to cervical cancer each year.

Not only that, but Zimbabwe’s Cancer Association also says breast cancer alone is claiming more than one thousand women every year.

Even health experts in the country concur that cervical and breast cancer have wreaked havoc in Zimbabwe.

Who is responsible?

Women rights activists have blamed the government for the deaths of their colleagues from cancer and other chronic illnesses.

“Government is solely responsible for the lack of service in hospitals especially in Matabeleland North and that means cancer patients are at the receiving end of the crisis in hospitals, “Fungisai Sithole from Citizen Health Watch said.

” What has worsened their plight even more is the government’s total neglect of critical illnesses in favour of Covid-19 and people are dying with little help at sight.”

For instance, all hospitals and clinics, including in resort cities like Victoria Falls, have no theatre for chemotherapy.

Patients must travel over 500 kilometers to reach the nearest facility at Mpilo Central Hospital, hence a few manage to take that route, Sithole noted.

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), outpatient consultations at public hospitals in Zimbabwe declined by 36 percent between April and July compared to the same period in 2019.

Is the government committed to fund hospitals?

Itai Rusike, the executive director of the Community Working Group on Health (CWGH), a network of community groups, said the upsurge in chronic illnesses and the advent of Covid-19 had put pressure on a health delivery system already weakened by over dependence on donors, intermittent strikes by doctors and nurses and minimal investment from the government.

“Covid-19 has been a wakeup call for countries with weaker health systems, especially those that have been relying on global donor funding, and this is what we are witnessing in Zimbabwe,” Rusike said.

He explained that Zimbabwe’s national budget in the past has seen very little money being allocated towards health and relied on donors.

“This left the country more vulnerable and exposed to disease outbreaks,” he said.

Last year, Zimbabwe’s budget allocation for health was US$4.80 per capita, almost 90% lower than the US$36 advised by the World Health Organisation (WHO), leaving many public health facilities without medicines.

The inadequate budgetary support has also been blamed for the brain drain in the health sector with doctors and nurses leaving for better paying jobs in other countries.

Rusike said when Covid-19 arrived, the country immediately shifted its focus wholly towards the pandemic.

“This is why we are witnessing more and more numbers of malaria deaths and maternal deaths alongside rising HIV and Tuberculosis cases,” he said.

The number of new coronavirus infections had been declining since August, leading to the relaxation of strict lockdown restrictions, but the crisis in the health sector and the emergence of the new Covid-19 Omicron variant is far from over.

Strikes, poor remuneration ground hospitals

Public hospitals are struggling in Zimbabwe because apart from lack of funding for health, they have also faced intermittent strikes by health care workers over deteriorating working conditions.

At the height of the Covid-19 lockdown in March, health workers including nurses and doctors went on strike for three months, which left public health institutions operating with skeletal staff during a global pandemic.

They led boycotts over the lack of medicines at hospitals and poor provision of personal protective equipment.

During the same period, many health workers also exited the country to seek greener pastures in European countries.

But there are fears that many people died in their homes from chronic diseases such as cancer, malaria, HIV\Aids as health facilities turned patients away, meaning these deaths would have gone unreported, according to Zimbabwe Nurses Association (Zina) president Innocent Dongo.

The collapse of the health system has also fueled clashes between health care workers and the government.

Zimbabwe’s Vice President Constantino Chiwenga, who is also the Health and Child Care minister, ordered the sacking of nearly 1500 nurses in November last year for rejecting his ministry’s cancellation of flexi hours for nurses.

Under the arrangement introduced a year-ago, following complaints by health workers that they cannot afford transport fares to work on their meagre salaries, hospitals introduced a two-day working week for nurses.

But the Health and Child Care ministry in memo to heads of public hospitals said the introduction of flexi hours had resulted in a lack of “continuity of nursing care in hospitals, compromised quality of patient care and exaggerated shortage of nurses resulting in inadequate ward coverage.”

Through their union, (Zina), the health workers have since gone to court about the issue.

But the strikes, boycotts, and limited resources, as well as Covid-19, have all led to reduced prevention programmes in the traditional hotspots of chronic illnesses such as Matabeleland North province, according to Rusike.

According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the most frequently occurring cancer among Zimbabweans is cervical cancer, followed by breast cancer. Among women alone, cervical cancer made up 28.9 percent of cancers in 2018, while breast cancer accounted for 17.1 percent

For men, the most common cancer is prostate cancer, which accounted for 20.1 percent of all cancers in 2018, followed by kaposi sarcoma, a form of skin cancer, at 15.2 percent.

According to Zimbabwe’s Registry, from 6 548 registered cases of cancer in 2013, figures shot up to 17 465 in 2018.

Meanwhile, VP Chiwenga, recently said plans were still afoot to create the Universal Health Cover that will exist side by side with medical aid societies to cushion chronically ill patients like Mhlanga Ngulube.

Slider3 years ago

Slider3 years ago

National4 years ago

National4 years ago

Opinion3 years ago

Opinion3 years ago

Tourism and Environment4 years ago

Tourism and Environment4 years ago

National2 years ago

National2 years ago

National3 years ago

National3 years ago

National2 years ago

National2 years ago

National4 years ago

National4 years ago